avril 18, 2024

Actu

Culture

Divertissement

Emploi

Environnement

Société

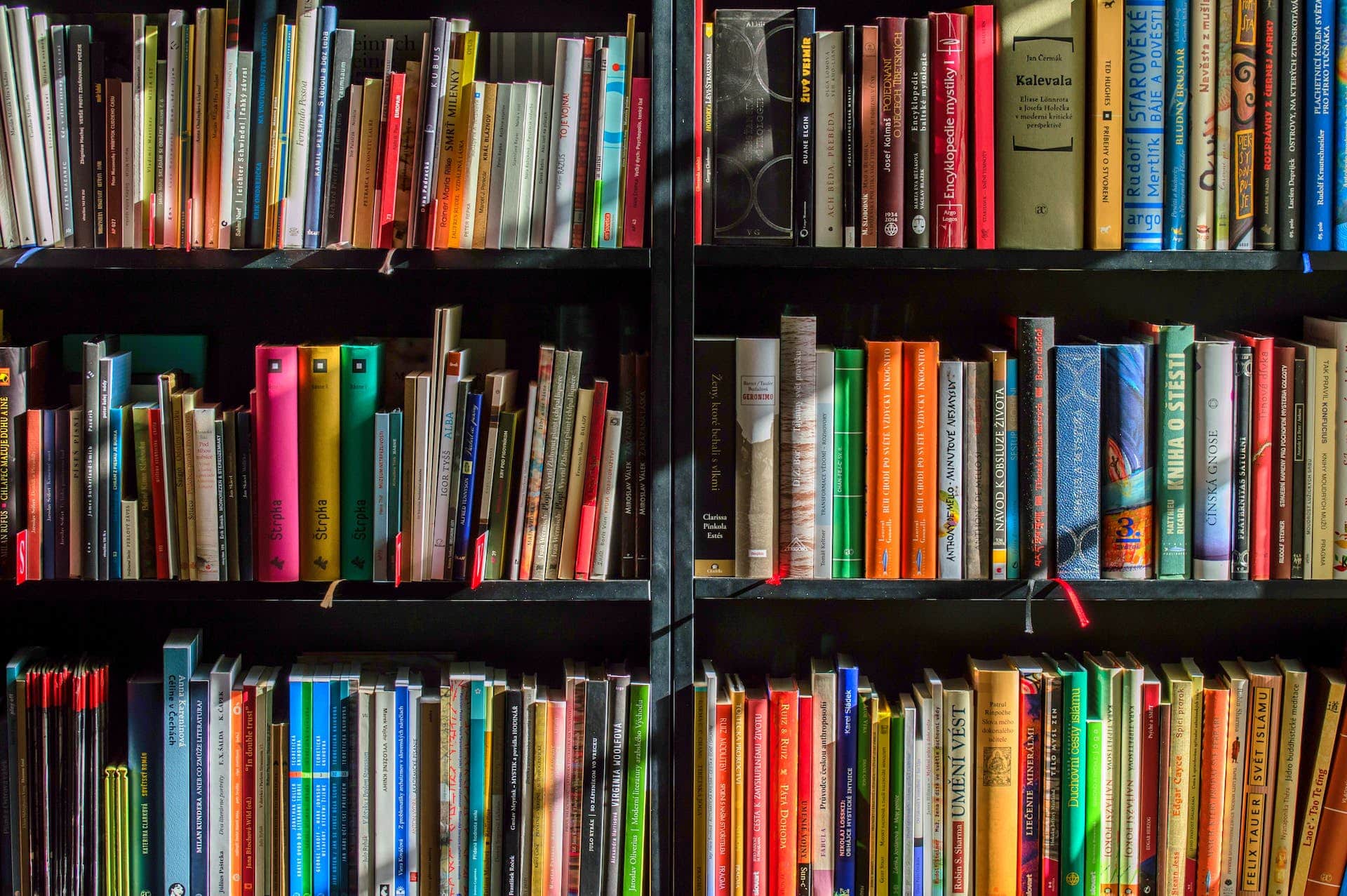

Comment les bibliothèques peuvent-elles s’adapter pour devenir des centres communautaires polyvalents ?

Aujourd’hui, nous allons aborder un sujet qui concerne un lieu que vous avez certainement fréquenté au moins une fois dans votre vie : la bibliothèque....

décembre 30, 2023

Copyright 2024. Tous Droits Réservés